Hispanics Expected To Show Support For Ron Rivera, Panthers At Super Bowl 50

By Tulup Gómez

Viva Rivera.

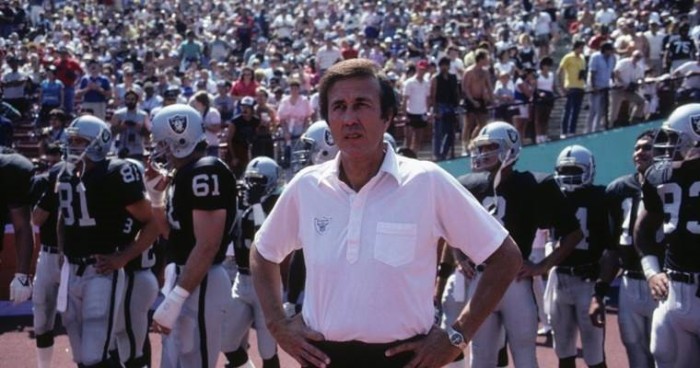

NFL Coach of the Year contender Ron Rivera and the Carolina Panthers are expected to have the support of the Hispanic community when they play the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl 50 next Sunday.

Rivera is Hispanic, raised by a mother of Mexican descent and a father whose family still calls Puerto Rico home.

With Rivera now in his fifth year at the helm, the Panthers’ popularity has become so widespread in the Hispanic community they now employ their own broadcast team to call their games in Spanish.

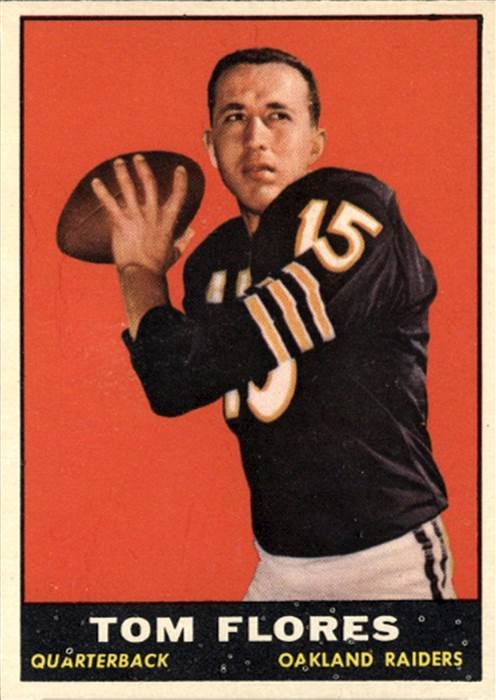

Rivera knows he isn’t the first Hispanic to coach in a Super Bowl — Tom Flores won two championships with the Oakland Raiders — but jokes he still feels like a “trail blazer.”

“For the most part it’s usually baseball and soccer [that are popular] there,” Rivera told the Associated Press. “But football is trying to become a world sport … So it’s neat to see that kind of support, and because of my parents’ heritage, there is a tremendous amount of pride.”

Randall Alexander Varnum, 29, from Mexico City, will be tuning in to watch the Super Bowl to root on Carolina. He’s been a fan of the Panthers his entire life. He even lived in Charlotte, North Carolina, for a while and attended some games.

“The fact they have Ron Rivera could be a factor for some fans to pay attention to the game, even if they’re not fans of either team,” Varnum said.

Esteban Rivera, 30, the sports editor for GFR Media in Puerto Rico, said there hasn’t been overwhelming support for the Panthers yet, but expects that could change once more people learn of Rivera’s heritage.

“Puerto Ricans usually support their own in sports, so Ron Rivera and the Panthers will be the favorites on the island,” he said.

Rivera was raised in a military family, a self-described Army brat. His parents met at a USO dance, the Rivera family moved from one military base to another, with stops in Maryland, Washington, Panama and Germany. But home base for the Riveras was always Fort Ord, California, a little over an hour’s drive from Santa Clara, the Super Bowl site.

“It is a homecoming of sorts,” Rivera said.

Rivera is known in Carolina as a player’s coach. He regularly walks through the locker room, where he feels most at home, having played nine seasons as a linebacker with the Bears, part of the Monsters of the Midway who ran roughshod over the NFL for the 1985 championship.

Pro Bowl tight end Greg Olsen said if players have concerns about the intensity of practice, play call suggestions or even personal problems, Rivera’s door is always open — and he’s always receptive.

“In this league everyone just assumes that in order to be a football coach that you have to be standoffish, secretive and a little bit of a (jerk) — but you don’t,” Olsen said. “You can have the ear of the entire organization by the way you go about your business and the way you treat people. And Ron is the perfect example of that.”

Olsen said because Rivera “treats guys like men,” he’s earned the respect of the locker room.

It helps too that Rivera has played the game and can relate to what players are feeling.

“He has high expectations, and his standards are through the roof,” Olsen said. “But guys take a lot of pride in upholding those standards because they don’t want to disappoint him.”

Rivera’s ability to relate to people is the result of his upbringing.

In moving from city to city, Rivera had to be outgoing to make new friends. He learned that skill through sports; he also dabbled in baseball, golf and tennis.

He became an All-America at California and was the Bears’ second-round draft pick in 1984. Cerebral and hard-working, it was no surprise Rivera ventured into coaching.

Bears coach Dave Wannstedt offered him an unpaid internship in 1997, and Rivera accepted. He quickly moved up the ranks, becoming defensive coordinator in 2004. Rivera reached the Super Bowl two years later, a loss to Indianapolis’ Peyton Manning — the same quarterback, of course, the Panthers (17-1) face on Sunday.

Rivera was passed over for nine head coaching positions before landing with the Panthers in 2011. After a slow start, he’s won three straight NFC South championships and is 37-15-1 during that span.

Every week during team meetings, the 56-year-old Rivera chooses one pivotal play from the previous week’s game and plays the Spanish broadcast version for his players. Most don’t have a clue what the broadcasters are screaming about, but they holler in delight upon hearing the call.

If the Panthers win the Super Bowl, Rivera is hoping it will generate even more interest in football within the Hispanic community, and maybe even convince some to play — or even coach.

“I tell people you can do anything you want,” Rivera said. “It doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from.”

Super Bowl day. How are Latinos showing for