Claim Game: U.S., Cuba Try to Hash out Differences over Property

By Nora Gamez Torres And Glenn Garvin, The Miami Herald

Faced with sorting out nearly six decades of financial claims and counterclaims against one another that run into the hundreds of billions of dollars, diplomats from the United States and Cuba last week resorted to a time-honored custom of their profession: They agreed to talk again later, then packed up their briefcases and went home.

The quick and seemingly unfruitful end to the first day of negotiations ever over the claims did not surprise experts on the thousands of claims, who say the difficulties of reaching a settlement are complex — perhaps even more so than achieving U.S. diplomatic recognition of Cuba last year, which required 18 months of secret talks, a complicated spy swap and even divine (or at least papal) intervention.

But the seeming indifference on both sides to establishing a brisk timetable for negotiations — they agreed only to meet sometime in the first three months of 2016 — baffled many observers.

“There is not that much time to put this together,” said Mauricio Tamargo, an Arlington, Virginia, lawyer and former head of the U.S. government commission that handled financial claims over property confiscated by Cuba.

“The Obama administration ends in a year. And Cuba’s economy is in a massive state of deterioration since Venezuela cut off its subsidies. The only reason Cuba is even willing to talk is that they’ve lost all the Venezuelan money.”

Without a settlement of the claims, normal trade between the United States and Cuba will be literally impossible — the U.S. embargo of Cuba cannot legally be lifted until about 6,000 claims of American companies and individuals totaling about $8 billion are satisfied.

And while some analysts say President Barack Obama might have some legal wiggle room to open holes in the embargo without congressional approval, he cannot bargain away the more than $3 billion in lawsuit judgments against Cuba won by American citizens who say their relatives were murdered by Castro’s security forces.

“Unless those judgments are paid off, it will be like a full-employment act for American lawyers,” said Nicolas Gutierrez, a Miami legal consultant who works on Cuban claims issues. “Every time a Cuban airplane lands at a U.S. airport or a Cuban ship pulls into a U.S. port, some lawyer will be there with legal papers to seize it.”

Cuban leader Raúl Castro, less bound by congressional action, judicial rulings or popular opinion, would seem to have a freer hand in negotiating. But Castro, who claims the United States owes Havana $302 billion in damages from the economic embargo and attacks like the Bay of Pigs invasion, has his own problems.

U.S. citizens are estimated to have owned only about 5 percent of the vast swaths of the Cuban economy confiscated by the Castro government. Agreeing to pay American claims would invite demands on Castro from all over the world — including a million or more Cubans living in exile — to pay for their property, too.

That’s not a hypothetical threat: Gutierrez is the U.S. representative for a Barcelona company, 1898 Compañía de Recuperaciones Patrimoniales en Cuba, which is signing up Spanish clients to seek settlements from Cuba. (Though Spain settled its claims against Cuba in 1986, some Spanish courts have ruled that the deal wasn’t binding.) Because Spain considers anybody with a Spaniard grandparent to be a Spanish national, that means most of the population in Cuba in the confiscation era is eligible.

“Remember, Cuba was Spanish territory until 1898,” Gutierrez said. “There was hardly a living Cuban in 1959 who didn’t have at least one Spanish grandparent.”

Even the most optimistic observers believe tiptoeing through the political minefields on both sides of the Caribbean will make settlement of the claims issue difficult. And they say it will be nearly impossible should a Republican win the White House next November.

“Technically, an agreement is possible within the 12 months,” said Richard E. Feinberg, a senior official on Latin American policy in the Clinton administration and author of a long Brookings Institution study of the property claims published last week. “At the first meeting, both sides put forward their opening, maximalist positions. That’s how negotiations begin.

“Now let’s see at the next round whether the two sides become more creative and begin to seek common ground.”

The property claims are at the root of the long-standing hostilities between the United States and Cuba. Some American-owned farms and ranches were among the first private properties confiscated when Raúl Castro’s brother Fidel seized power in Cuba in January 1959. For the next 18 months, the two governments traded tit-for-tat punitive economic measures.

They climaxed in July 1960 with a Cuban law authorizing the seizure of all businesses on the island in which Americans owned a majority interest, followed three months later with the Eisenhower administration’s decision to prohibit the sale of anything but food or medicine to Cuba.

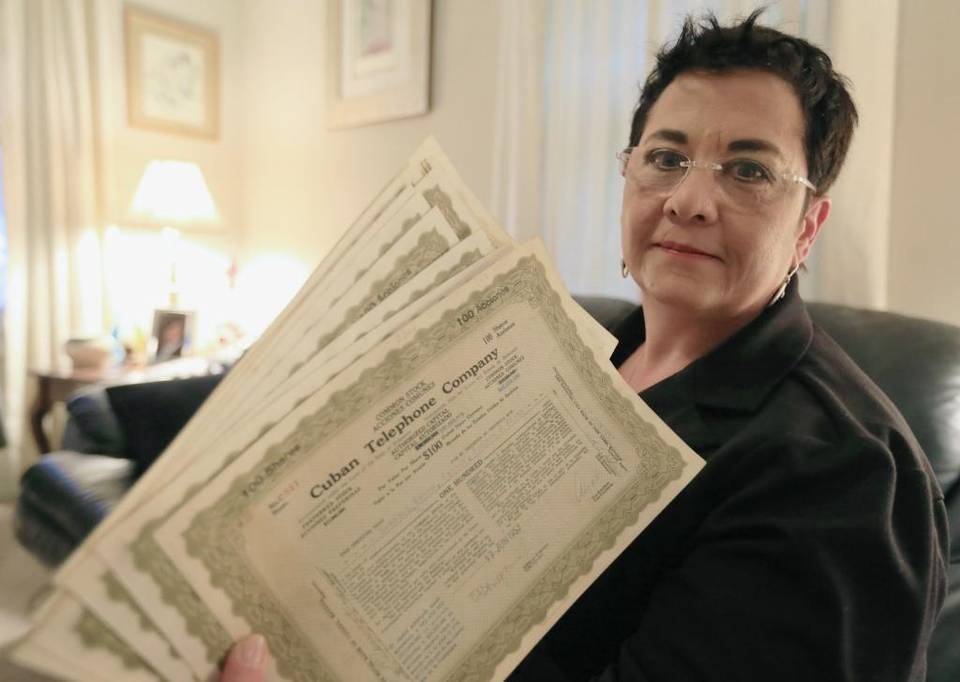

Because U.S. law generally prohibits suing foreign governments in American courts, families and companies that lost property in the confiscations had only one place to turn: the U.S. government’s Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, which manages American citizens’ demands for payment for property seized by other governments.

By 1972, when the commission stopped accepting claims, it had documented nearly 6,000 and set a value on them of about $1.9 billion. With the 6 percent interest the commission declared for unpaid claims, that figure has swollen to $8 billion.

But that $8 billion figure might shrink. For one thing, claimants have to maintain an unbroken chain of citizenship — that is, if an American company that lost a factory is subsequently sold to a German, the claim goes up in smoke. Since nobody has updated the claim commission’s files since 1972, it’s pure guesswork about how many of the claims remain valid.

It’s also possible that even valid claims could be settled for less than face value — the State Department negotiators who met their Cuban counterparts in Havana last week have the legal authority to strike binding bargains. And the Brookings study noted that in some previous sets of claims against Communist governments, the commission took much less: 10 cents on the dollar for U.S. property seized by the Soviet Union, 39 cents on the dollar for China, 45 cents for other countries in Eastern Europe. Sometimes no interest was paid.

On the other hand, Vietnam paid 100 percent of the principal and 80 percent of the interest for claims against it; Germany, 100 percent of the principal and 50 percent of the interest.

The Brookings study also suggested other solutions, including paying 100 percent of smaller claims by individuals — about 5,000 of them, totaling a relatively small $229 million before interest — while offering the 900 or so big corporate claims (about $1.68 billion before interest) exclusive business deals or property in Cuba.

Whether the chance to do business in a Cuba that, despite a few lurching steps toward private property and free-market business practices, is still fundamentally a communist country is all that attractive to corporations is dubious in the eyes of many observers.

“The Cubans could offer sort of substitution or alternative means of compensation,” Tamargo said. “That’s conceivable, that’s possible. . . . It’s doable if the Cubans are willing. But the problem is future safeguards and guarantees for the U.S. investor. There would have to be due process and property rights in Cuba, which right now, do not exist.”

While the property claims might be bargained down to lower levels by the State Department, it has no authority at all over another set of claims: damages awarded against Cuba in anti-terrorist lawsuits.

Congress in 1996 created a loophole in the prohibition on U.S. citizen lawsuits against foreign governments. In response to a growing number of terrorist murders and kidnappings of Americans, Congress permitted victims to go to court against any government on the State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism — which included Cuba.

A dozen or so Americans — many of them from South Florida — filed suits, and because Cuba refused to defend itself in U.S. courts, most of them won whopping default judgments, ranging up to $1.1 billion for the family of Havana GM dealer Gustavo Villoldo, who committed suicide in 1959 after all his property was confiscated.

Some of the early judgments were paid out of money owed by AT&T and other American firms to the Cuban state telephone company that had been frozen in an escrow account. But that money ran out, and more than $3 billion is still owed.

“I don’t believe there’s any way for the president or the executive branch to overturn those verdicts or cancel those judgments,” said Miami attorney Joseph DeMaria, who worked on several of the early anti-terrorism lawsuits. “That would be a bill of attainder” — a legislative act punishing someone without trial, a practice specifically outlawed in the U.S. constitution.

The verdicts, if left unpaid, could lead to a kind of legal guerrilla warfare against any kind of future trade between the United States and Cuba. Already, the State Department has had to help set up a complicated system to protect U.S. agricultural companies selling food to Cuba under one of the embargo exemptions from being raided by attorneys trying to collect on lawsuits.

For instance, ordinarily a company shipping a load of rice to Cuba from New Orleans would sign over the title before the ship left port. But out of fear that the rice (or the money Cuba paid for it) would be seized by a lawyer with an unpaid court judgment, American companies have to ship the rice without changing the title, then collect a Cuban letter of credit left in a Spanish bank, out of reach of U.S. subpoenas.

“Cuba has already had a couple of planes seized on the ground in the United States by clever attorneys, and the Cubans have had to get a lot smarter,” DeMaria said. “When they set up a new phone company, they made sure the owners of record were from France and Spain and other countries, so they wouldn’t get their money seized again.”

Some attorneys foresee legal attacks on U.S. companies attempting to do business in Cuba who unwittingly make use of confiscated American properties.

“That amounts to trafficking in stolen property,” Tamargo said, “and Americans, whether they know it or not, do it all the time. One of the runways at Josá Martí airport in Havana is built on a confiscated property. So is much of the port at Mariel, as well as Havana harbor — in fact, every major port in Cuba. Whenever anybody travels to Cuba and engages in commerce there, it’s my opinion they are trafficking in stolen American property.”